- Home

- Jessica Verdi

And She Was Page 2

And She Was Read online

Page 2

“It was really good,” I say. Normally, I’m happy when she asks about practice, but today I kind of wish she hadn’t, so I could have started with the passport stuff like Sam and I planned.

“Glad to hear it.” She doesn’t pause in her task.

A sealed package rests on the counter. I recognize the box immediately, and it’s like a railroad switch—the only thing that could get me to veer onto a different track right now.

“Hot Sauce King!” I cry. I grab the box and bring it to the table.

That gets Mom to put her scissors down. Her eyes light up. “I was waiting for you to open it. What do you think—wait until fajita night tomorrow, or taste test now?”

“Taste test now!” I grab the scissors and slice through the packing tape. Mom gets up and grabs six teaspoons from the silverware drawer. A deep respect and admiration for spicy food is one quality Mom and I share unreservedly. A few times a year we order new hot sauces online and have a tasting party.

There are three bottles inside: Knock-You-on-Your-Butt Spicy Sauce, Fire Mouth Habanero, and Chef José’s What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Stronger. I’ve been wanting to try that last one for a long time. Mom and I make quick work of opening the bottles and pouring a small amount of each into the teaspoons. When they’ve all been doled out, we each pick up the Knock-You-on-Your-Butt and face off like we’re going to thumb wrestle.

“Ready?” she asks.

“I was born ready.”

“One, two, three!”

We spoon the sauce into our mouths. My eyes immediately water, and Mom forces herself to swallow before breaking into a surprised cough.

“Holy crap,” I croak.

“That’s a nine at least,” she says, taking a giant gulp of water. Rookie move—water doesn’t do much to cool your mouth in times like these. Laughing, I go to the fridge and pour us each a big glass of almond milk.

I take a sip, smack my lips, and say, “Eight.” We always rank the sauces on a scale of one to ten.

When our palates have sufficiently recovered, we move on to the Fire Mouth Habanero. We both agree this one is probably about a five, though someone with a weaker constitution would probably give these all a ten. The What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Stronger is way more up my alley—I give it a nine; Mom a ten. I don’t know why I love the sensation that my taste buds are burning a fiery death, but I do.

“We’re ordering more of that one next time,” I say, tossing the spoons in the dishwasher.

“Definitely.” She slips her coupon pouch into her purse, grabs her insulated lunch bag from its hook on the pantry door, and starts pulling sandwich fixings from the fridge—a telltale sign she’s about to start a shift. She works in the ER and doesn’t always get to take an official dinner break. “So, Niya was telling me about this new movie she and Ramesh just watched. It’s a documentary about a guy who had to get his leg amputated, but kept it—in a grill, of all places. And then the grill was sold, and the new owner found the leg and refused to give it back.” She grins over her shoulder. “We should watch that one night next week if you’re free.”

“Sure,” I say. “Maybe Monday after I get home from the juice stand?”

“Works for me.”

It’s easy, hanging out with her like this. Our relationship is like a coin, and these are what I call “heads-side” moments. Both our schedules are nuts and we don’t always spend as much time together as we’d like, but we do make sure to set aside time for our traditions. Puzzles together on the front porch when the weather is nice, Netflix on lazy nights, going out to restaurants for special occasions and ordering the spiciest things on the menu, occasional homemade dinners with Sam and his family. I know if I’m ever in trouble, Mom will be there for me. We’re a team. Not quite a doubles team, where everything one of us does depends on the other, but more like singles players representing the same country in the Olympics. A team in which the members operate independently, but with a shared goal.

But I know the second I broach the topic of the passport and Toronto, the coin is going to flip. And the tails side is a completely different story. A wall goes up between me and Mom, and we might both still be competing in the Olympics, but we’re bitter rivals. Sometimes this happens when the subject of the past comes up—she doesn’t like talking about her family or where she came from, and she always shuts down in those moments. But the main thing that sends the wall up is tennis.

Mom has absolutely no faith that my tennis career is going to happen. For a long time, she humored me, and drove me to practice as if it were just another mom job like doctor’s office visits and parent-teacher conferences. But lately, any time the subject of my going pro comes up, she goes on the offensive, saying it’s too expensive or unrealistic. I actually think she’s hoping I’ll fail so she’ll be able to insist I go to college in a year. She had to go to work right after high school, and she wants me to have the education, the opportunities, she never had. And yes, in lots of ways, it makes sense to play tennis at the collegiate level. Mom would be happy I was “continuing my academic career,” and I’d be happy to have regular sessions on the court. The school could finance a lot of my tennis expenses. Plenty of pros played in college. It’s a viable path to the majors for sure.

Except for the tiny fact that it doesn’t feel right. I’ve never been a very dedicated student—I don’t think I ever got higher than a B– in anything except phys ed. The court was always my classroom; training was my brand of studying. Commencement never meant a beginning—it meant the end of my biggest distraction. While Sam and most of the other kids in our year were obsessing over transcripts and portfolios and letters of recommendation this past fall, I didn’t apply to a single college. I’m done with school and can finally focus on the important stuff. So why on earth would I go back?

I grab an apple from the basket on the windowsill, spin it around to remove the stem, and watch Mom as she drops a handful of baby carrots into a baggie. I don’t want to flip the coin; I don’t want this good moment to come to an end. But I have to. It’s too important. I take a deep breath and segue into the line I’d practiced in the car with Sam: “I’m going to apply for a passport next week. Would you mind digging up my birth certificate when you get a chance? I’ll need it for the application.”

Like a sponge being zapped of its moisture, Mom’s entire body goes rigid. The baggie of baby carrots slips from her fingers to the counter. One of the little orange nubs rolls into the sink.

Really? Already? I didn’t even mention the word tennis. “What’s wrong?” I ask, the lingering hot sauce on my tongue turning sour.

“Nothing.” She turns to face me. Her expression is hard to read—unlined, but oddly tense. If I didn’t have so much practice spotting and analyzing abrupt actions in short bursts of time, I’d miss the swift lick of her lips, the extra beat she takes to make sure there’s no emotion in her voice. “What do you need a passport for?”

“Well …” I take a realigning moment of my own. Forget the ease-her-into-it strategy. Just say it. “Now that school’s over, Bob and I agree it’s time to start entering pro tournaments. I know we’ve talked about how it’s not possible, but I think I need to make it possible. The only way I’m ever going to reach the majors is if I start earning ranking points now. I can’t stay in Francis forever.”

“Most eighteen-year-olds go off to college when they want to get away from their hometown,” Mom says under her breath. I ignore it.

“I know money is tight. But I’ll take more shifts at work, and then use that money for travel. I’ll subsidize it with credit cards if I have to. The most important thing is playing, getting the experience, getting my name out there, and getting ranked.”

The corners of her mouth have turned down.

I keep going. “There are some tournaments in the States coming up, but Bob said it would be smart to begin with the one in Toronto in August.” I pause briefly. “That’s where the passport comes in.”

She tak

es the apple from where I abandoned it on the table and carefully puts it back in its basket. Everything in its place.

“What do you think?” I ask finally.

She looks at me. A flash of sadness floods her eyes, but then it quickly subsides, like the changes of a tide sped up on a time-lapse video. “I don’t see how it can work, Dara.”

My heart drops. This is so unfair. Why can’t she even try to see it from my point of view? “Why not?” I ask flatly.

“First of all, how are you going to both take on more shifts at the juice stand and travel so much? There are only so many hours in the day. Believe me, I know.”

“Well, I won’t be traveling all the time. Each tournament is only six days. I could—”

“Secondly, please don’t put any of this on your credit card. Those bills accumulate faster than you can imagine. And the interest rates are outrageous. I’ve worked very hard to keep us out of debt. Credit cards are for—”

“Emergencies only,” I mumble. “Yeah, I know.” This is not the first time I’ve heard this speech. But doesn’t she understand that this feels like an emergency to me?

She checks the clock on the microwave. “I have to go.” She grabs her lunch bag, but stops before leaving the kitchen and pulls me into a hug. I don’t back away, but I don’t relax into it, either. “I’m proud of you, Dara. We just need to be more … realistic.” She ruffles my hair and leaves the room.

No. She doesn’t get to just shut me down like this. She doesn’t get to pretend like she cares and then walk out the door, leaving me stuck and alone. Not again.

I run after her. “Can I at least have my birth certificate so I can get my passport? Maybe I do have to come up with a better plan, but when I do, I want to be ready to go.”

Her hand is on the screen door latch, and she only turns halfway back. She doesn’t look me in the eye. “I’m sorry, I don’t know where it is.” With that, she leaves.

I stare at the screen door as it groans shut.

She lost my birth certificate?

Or does she just not want to give it to me? Fury burns hot through my veins. I’m eighteen. I don’t have to listen to her. I can do what I want. If I want to rack up a million dollars in credit card debt, that’s my own damn prerogative.

Once Mom’s car disappears down the road, I spin on my heel and march straight to her desk in the dining room.

Pay stubs, old report cards, checkbook, tax documents.

No birth certificate.

I go to the living room and pull my baby book off the bookshelf. A few photos of me as a baby, an inked footprint, a lock of hair from my first haircut. No birth certificate.

Where else could it be? I worry my bottom lip with my teeth, a bad habit that tends to show up when I’m unsure about something.

There’s no clutter in this house. No secret places it could be hiding. For someone who doesn’t spend much time at home, Mom sure loves cleaning the place. From the hints I’ve managed to eke out about her past, I know her parents were abusive, and she moved out after high school and never spoke to them again. And as for my father … Turns out knowing someone’s last name isn’t a prerequisite for him to get you pregnant. I think it brings Mom a feeling of peace, of control, to keep the house in perfect order. But that just makes it even more unbelievable that she really “doesn’t know” where my birth certificate is.

My legs start moving again, this time toward Mom’s room. Her nightstand contains books, a book light, an economy-sized bottle of moisturizer, and some lip balm. No documents of any kind. I swipe the lip balm and glide a healthy coat on my chewed, cracked lips, then put it back. Her dresser drawers are filled with folded squares of underwear, T-shirts, jeans, and scrubs. Her closet is neatly arranged with shoes in cubbies, coats and dresses on hangers. I drop to my stomach and use the flashlight on my phone to check under the bed. Orderly boxes of winter clothes. I’m about to stand back up when the flashlight beam glints off something small and shiny at the back next to the wall. I shimmy closer, my hair clinging to the staticky underside of the bed’s box spring, and stretch to reach the object.

When my fingertips graze the surface, my pulse beats a triumphant little staccato. Jackpot. The light had caught on the metal of a small lock. And the lock is latched onto a safe deposit box–looking thing. There’s no way my birth certificate isn’t in there.

I slide out from under the bed, bringing the box with me, and push my hair away from my face. I sit back on my heels and try to pull the lid open. The lock is secure. The empty keyhole yawns at me like a bored kid in church.

The first question that comes to mind: Where is the key?

And then the second: Why would Mom have a locked box under her bed at all? God knows we don’t have any valuables that would need to be kept safe from potential robbers. I don’t think I’ve ever even heard of there being a burglary in this town anyway. What could she possibly be hiding? My mother isn’t the most open person in the world, but she’s also pretty basic: work, sleep, Once Upon a Time on Sunday nights. Repeat.

I do another search through the house, this time for a key, a small one that might fit in the lock of a mysterious secret box.

I check all the logical places first: desk and kitchen drawers, the tops of bookshelves, the “miscellaneous” basket near the refrigerator. Then I look in the illogical places: the toes of boots, the zippered opening in throw pillows, the ice bin in the freezer.

I’m beginning to think either the key doesn’t exist or Mom has it with her at the hospital when, on my third sweep through her room, I find it. I blink a few times to make sure it’s really there and not just a trick of my tired eyes. It’s small and silver and nestled comfortably under the bottle of moisturizer on her nightstand. Smiling pleasantly up at me like I’m an idiot.

I’d laugh if this whole day wasn’t so frustrating.

Sitting on the floor of my mom’s bedroom—this has to be the most time I’ve ever spent in here—I slip the key into the lock and turn.

It clicks, and I lift the lid. The box is very full.

On the top of the pile are two small prescription bottles. I don’t recognize the names of the meds, but they’re both in Mom’s name, and the filled date is only a few weeks ago. She didn’t tell me she was sick. And why wouldn’t she just put the medicine in the kitchen where we keep the rest of our pharmacy stuff? Why would she lock it away …?

Oh God, she isn’t sick sick, is she? What if she has cancer? What if she’s been dealing with this all alone because she didn’t want to scare me, and was waiting to tell me the truth until she got her official prognosis? What if that’s the reason she doesn’t want me to go pro—because she might need someone to take care of her?

My skin prickles as the image of Mom not being here anymore invades my mind. She’s all I have. I grab my phone and begin to dial her cell. Whatever happens, I’m here for you, I want to say to her. Nothing’s more important than this.

But a dose of rationale trickles in and, before I hit the green “call” button, I switch over to the internet browser and look up the names of the medications. Huh. One is an estrogen replacement. The other is a testosterone blocker. So … not cancer? Looks like she has some sort of hormonal imbalance I didn’t know about. Maybe she’s gone into early menopause. That could explain why she’s been so cranky lately.

My breathing returns to normal as the panic seeps from my body. She’s fine. Everyone’s fine. I wish she didn’t feel like she has to shelter me from this stuff. I’m not a little kid anymore. I can handle it.

I place the bottles on the carpet and return to the box’s contents. It’s mostly papers. I shuffle through, looking for something that might be a birth certificate. It feels kind of wrong to be snooping in here, going through all of Mom’s personal stuff. I already know about one thing she didn’t want me to; at this point I just want to find what I came for and be done with it.

Toward the bottom of the pile of documents, I find it. New York State Certifica

tion of Birth. Yes! First step toward getting my passport—and my freedom—complete.

But as I skim the information on the document, my celebration drifts into confusion.

My first name, middle name, and birth date are correct. But nothing else makes sense. The child’s name is listed as Dara Ruth Hogan. That’s not my name. My name is Dara Ruth Baker.

And the parents’ names. Not only are there two of them, when Mom always swore she didn’t know my father’s name, but … neither of them is Mom.

Father’s name: Marcus Hogan.

Mother’s maiden name: Celeste Margaret Pembroke.

Where is Mellie Baker?

I stare at the paper. It shivers in my wavering grasp. But no matter how many times I read the words on the page, no logical explanation comes. I don’t understand what I’m looking at. The only thing I know for sure is that she never planned on me seeing this.

I take every last item from the box, spread them out on the carpet, and begin to read. With each photo and document, the disquiet in my stomach becomes sharper, jagged.

A wedding announcement for Marcus Hogan and Celeste Pembroke from just months before I was born.

An old, worn issue of Sports Illustrated that falls open to a half-page feature on men’s tennis up-and-comers. The names mentioned include Marcus Hogan.

And dozens of pictures I’ve never seen before of two people and a chubby-armed baby. There’s no question: The baby is me. I recognize myself from the pictures in the baby book, and I still have that dimple under my left eye when I smile. Mom’s not in a single photo.

I sit back a little. Force myself to take five breaths. Then, carefully, I reach for the photos. Study them.

They span at least six months—mushy newborn up through the start of the cute drooling phase. They were taken in different locations at different times of year. And I’m always with the same two people. A man and a woman. No one else. No Mom.

The man is clean-shaven, with shaggy, light-brown hair and blue eyes. There’s something about his smile that is familiar, but I don’t think I’ve seen him before. The woman has long, wavy blond hair, pink lips and cheeks. She looks so much like me, right down to the dimple, that it takes my breath away.

Follow Your Arrow

Follow Your Arrow What You Left Behind

What You Left Behind My Life After Now

My Life After Now The Summer I Wasn't Me

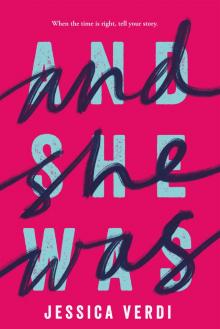

The Summer I Wasn't Me And She Was

And She Was